The Confluence of Design & the Social Sciences

By Madalyn Yovanoff | Senior Designer, Philadelphia Studio

The sociology of space and architecture—how the built environment can cue and support positive individual or group behaviors (or negative behaviors for that matter) and what that means for the workplace—was a major factor inspiring my choice of design as a profession. In 2023, as an IA Spark Research Fellowship recipient, I explored in-depth the development and confluence of design and the social sciences.

To support more informed design decisions, key goals were the cataloging of information applicable to interior design and architecture for a deeper understanding of the sociological and psychological impacts of space on users. Additional objectives were the creation of guidelines to apply that knowledge base for human well-being and design excellence, as well as to advise clients and develop design innovations.

As I worked my way through a plethora of books, journals, and internet resources, the history and derivation of many fundamental concepts and terms well-known in the design industry emerged.

Historical Context

Although some ideas we recognize today as sociological thought can be traced back to ancient Greece, the term Sociology was first used in the late 1700s, defined more explicitly in the 1830s as a study of social structures and functions. Soon, Psychology as a field emerged focusing more specifically on individual mental processes and behaviors.

Eventually, these disciplines led to the application of social theory to architectural design. As early as the 1950s, scientists began to explore neuro-architecture, studying how space affects the brain on a physiological level, although significant advancement was stymied till the advent of more sophisticated brain imaging in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Environmental psychology was not fully recognized until the late 1960s when scientists began to explore the correlation between human behaviors and environments. And around 2000, Neuro-esthetics came along, defined as the neuroscience of the aesthetic experience and cognition, generally focused on the positive physiological effects of interacting with art and the impact of different modes of perceived beauty.

In terms of human history, the behavioral sciences are therefore very young, especially as they relate to architecture and design. The most relevant explorations of that relationship have occurred within the last 75 years, with much of the existing work yet to be fully understood, agreed upon, or directly applied.

Key Concepts

However, several key concepts and terms coined by the social sciences are fundamental to current design thinking. To name a few:

- Proxemics describes a form of nonverbal communication based around the use of space, the distance people feel necessary to maintain between themselves and others depending on their relationship, and the way spaces are designed for various types of interaction. This is where the idea of personal bubbles came from based on typical comfort ranges for interaction in Western cultures, including nuanced guidelines for details like ceiling height or whether a person should be seated or standing.

- In the late 1970's, with the work of environmental psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan frameworks for human spatial preferences emerged, emphasizing concepts of nature and biophilia. Ideas like coherence and complexity and prospect and refuge, acknowledge the human need for safe as well as logical spaces that are engaging and stimulating.

- The social logic of space pioneered by professors Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson was a seminal effort that advanced our understanding, language, and application of previous concepts around major ideas like co-presence (physically being in the same space), stranger vs inhabitant (exploring ideas about territoriality, belonging, and agency), isovists (how the volume of space visible from a given location, such as a corridor, can affect perceptions and behavior), and transpatial (the idea that some relationships, affinities, or professions can actually bridge spatial divides if the need to interact is important enough).

Confidential Client, McLean, VA | Photography by Todd Mason

Today, applications of these concepts to spatial design must also accommodate diversity, well-being, complicated goals, and productivity, as well as spatial logistics making workplace design particularly complex. Personality types, neurodiversity, and preferences based on gender or cultural background, as well as enterprise objectives, company culture, and brand, require unique approaches and outcomes for each design project.

Confidential Financial Client, New York, NY | Photography by Magda Biernat Photography

Despite the impact of the findings of the social sciences, multiple interdisciplinary connections between the sciences that could contribute to spatial design have yet to be made, and often the work of psychologists and sociologists is not directly applicable to architectural decisions. Scientists tend to focus on particular closely-defined interests, which rarely intersect with the specific needs of designers.

Notable Research

Still, a few researchers are working squarely in the design realm. At the Bartlett School of Architecture at UCL in London (in 2024 for the second year running, ranked #1 in the world for architecture and the built environment), Dr. Kerstin Sailer is a good example. Highlights from the work of Sailer and her colleagues over the past five years speak for themselves.

For example, since study results on open office environments have been hard to quantify because they cover many types of open office environments without differentiation or taking into account nearby resources or team members, Sailer’s team analyzed three specific types of office spaces via case studies—the cubical-open-office, the benching-open-office, and private-office setting. Whatever the format, the conclusion was the same: layout has to correlate with organizational needs, reinforced through company culture. Physical space and organizational structure need to be considered as one.

Another study on the open office with clearly defined parameters tracked perceptions of productivity based on positions in the space. Factors included considerations like isovists (mentioned above), proximity to windows or walls, having your back to a wall, or being in a middle seat. Key findings showed that the number one spatial correlation in perceived productivity was the ability to sit with your back to a wall. The second important factor was the number of people in your field of vision. Perceived productivity increases when fewer people are visible. Accordingly, the best scenario provides a significant number of visual barriers within larger spaces where users can sit with their backs to the barriers without seeing too many people in front of them.

In several papers in response to the recent pandemic, Sailer spotlighted the multiple pain points of hybrid work, especially important since so many companies have had to adapt to a hybrid model without much forethought. Based on these realities, she devised an evidence-based decision-making table and a framework of parameters for organizations. These papers address the tension between choice, need, and well-being, including the impact of individual choice on others, as well as the shortcomings of technology in supporting social connections and the realities of proximity bias.

The Behavioral Sciences and Spatial Design

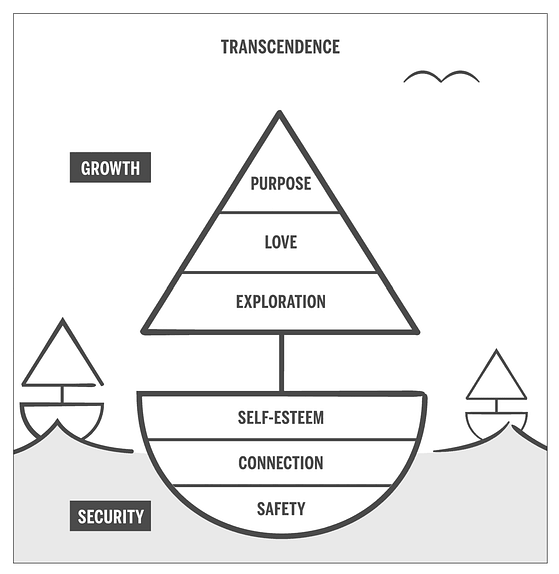

Incorporating the findings of social science into spatial design draws on multiple threads of research as well as Maslow's classic Hierarchy of Needs Theory. A new graphic representation of that hierarchy represented as a sailboat conceived by cognitive scientist Scott Barry Kaufman is gaining recognition since it addresses the nuances and complexities of social theory more fully than the traditional pyramid—particularly the fact that human needs are always in flux, rather than static.

Belonging

Starting at the base of the boat, after basic physiological and safety needs are met, belonging is considered the next imperative for positive workplace outcomes, emphasizing three factors—spatial structure, user dignity, and ownership.

Source: “Transcend” by Scott Barry Kaufman / Sailboat illustration by Andy Ogden

The structural framework of space hugely affects the individual and collective sense of identity and dignity. To that end, the hybrid model adopted by many enterprises layers in even more complexity, including the effects of proximity bias for those physically present—users sharing spaces are more likely to feel affinity towards one another than those who are not present. Hence, the importance of providing an alluring space for face-to-face engagement and to celebrate the enterprise.

Lerma Advertising, Dallas, TX | Photography by RW Collective, LLC

Furthermore, nurturing dignity through the use of space means giving users some level of personal ownership, involvement, and agency over their environment—this space is for you as opposed to you are allowed to be in this space. A sense of ownership creates significant satisfaction based on territory as does the amount of space allocated per person. Maintaining a comfortable space bubble around each user as well as delegating some control over an area or type of space is important.

Engagement

And, since many workers now spend less time at the office, space for culture building, community, and engagement is particularly called for, begging the question of motivation—what causes people to come to a space and participate, rather than just pass through?

Engagement and purpose is key. Prioritizing and allocating spaces that support recognition, mentorship, community, and the value of the work being done is critical. Within the space preference frameworks are significant for stimulation and engagement—a balance between safety, mystery, biophilic preferences, and experiences of art and beauty.

Now more than ever, the office is focused on social connections and in-person collaboration. Factors that connect people include inviting places to linger and interact balanced with the ability to set boundaries and retreat to focus areas, all integrated through intuitive circulation strategies.

Confidential Client, McLean, VA | Photography by Todd Mason

Authenticity

With Gen Z entering the workplace, authenticity has taken on a new importance requiring organizations to genuinely be who and what they say they are, building a mutual synergy between culture, staff, and consumer base. Also, providing a level of flexibility and control for employees emphasizes mutual respect. Allowing ownership of territory (noted above) inherently generates a sense of power, as does the customization of space to better support preferences or initiatives.

Confidential Client, McLean, VA | Photography by Todd Mason

Aligning an organization’s goals with spatial design is critical for functionality as well as the communication of culture and purpose. If not achieved, an immediate sense of inauthenticity is established. A space that does not function to support its stated goals generates a sense that the outcomes users are trying to produce are invalid.

And, the design of space is one of the greatest opportunities to continuously communicate brand identity and culture. Going beyond graphics and logos, the office lay out itself must support and communicate authenticity, company ethos, and goals. The alignment of space with activities valued by the enterprise and its culture speaks to the organization’s priorities.

Confidential Client, Brooklyn, NY | Photography by Robert Benson Photography

What’s Next?

Part of finding the answers we need is framing the question. And there are a multitude of questions yet to be asked of the social sciences. A logical next step might be leveraging partnerships with the academic community to advance data collection and actionable knowledge. This could manifest in a variety of ways, whether that be hiring a social science specialist on the design team or aligning with a team grounded in behavioral sciences to do focused research. Partnering with an academic institution is another possibility. That could lead to observational studies with specific and quantifiable parameters, surveys with detailed focused questions, and in-depth case studies that go beyond typical post-occupancy documentation.

The designed space itself, though powerful, must be based on forethought. It is a hugely significant percentage of the equation, but to achieve maximum potential, projects need a robust strategy that ensures the space is genuinely tailored to organizational goals, users, and empowered for positive engagement.

IA is committed to that endeavor, growing and applying a robust knowledge base around spatial design that includes the findings of the social sciences, which we believe will ultimately drive a significant shift in how spaces are designed, why spaces are designed, and most importantly, how spaces positively impact those who use them.

For our professionals, I have put together a quick guide as a checklist of key considerations when designing a space. Some of the considerations may not align with everything a client is asking for or might even conflict with client directives. But such tensions need to be acknowledged openly as we consider how to strategically address and optimally engage the social sciences behind user needs and perceptions, moving the practice of design and architecture forward for user well-being and enterprise productivity.