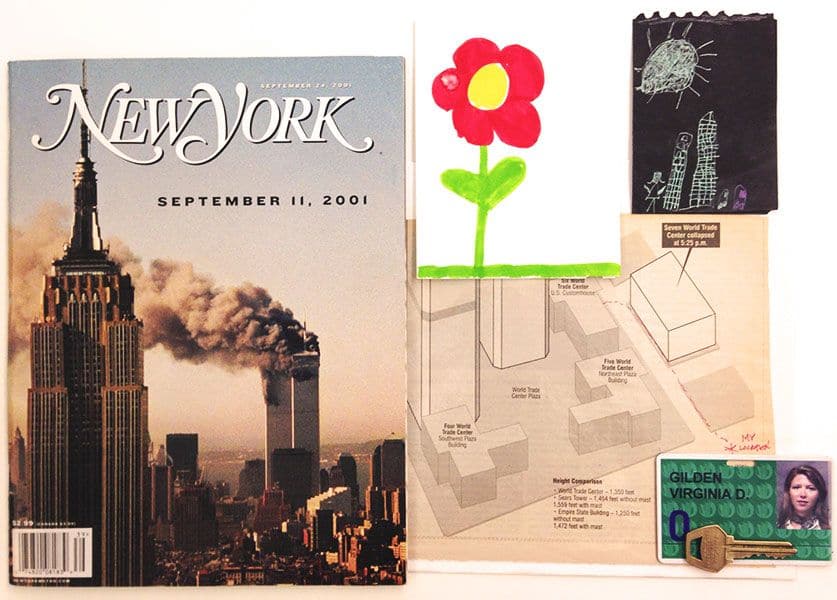

On September 11 in 2001, Ginger Gilden, now a senior designer with IA Interior Architects, was commuting to her office in Tower One of Manhattan’s World Trade Center. She had started working for an architecture and interior design firm in the building one month earlier, and was arriving behind schedule due to a late night on September 10.

I arrived via subway at the World Trade Center around 8:45 am, 15 minutes behind my usual schedule because I had taken a later train to work. When I arrived, I heard what sounded like a boom from outside, followed by a lot of commotion. There was a mall beneath the trade center, and people were running from that into the subway. There was only one doorway out to the street. We filed one-by-one through the turnstile above ground, when people started yelling “Get away from the building!” There were pieces of the building, hunks of steel, lying all over the street. And when I looked up, I could only see black smoke billowing out of the tower and I thought to myself “Wow, that’s a really big hole.” But that was all I could see, so I ran across the street and when I looked back at the building there was all this paper flying out of the hole, and junk, and smoke.

I watched the second plane coming, for a long time it seemed, and I thought there was something wrong with the flight towers. When it hit the building I could feel the heat, and smell the jet fuel. It was like watching a movie, with all five of your senses stimulated. It’s sort of like your adrenaline kicks you into survival mode, and you start thinking, “What do I do next to make myself safer?” I didn’t have kids at the time; it was just me. I knew I didn’t want to run with this massive crowd fleeing form the Trade Center in all directions. I knew it wouldn’t be safe. So I covered myself with my bag on the side of a building on the corner of Church Street and Vesey Street. Once the crowd cleared, there were shoes and bags laying everywhere—people literally ran out of their shoes when they took off in total panic. The only people left on the streets were cops who kept saying, “Get out of here! Get out of the neighborhood!”

From Church Street, I walked over to Broadway, where I recognized one of my new colleagues. There were thousands of people like me on the street that day. As we were walking, we’d come across someone who was really upset, and a group of people would go over to them, console them, and take care of them to make sure they were okay. People were handing out water left and right and asking “Do you know where you need to go?” “Is there something I can do?” Cars on the street had their doors open with radios broadcasting the latest news developments so you could sort of hear what was happening as you were walking by.

I hadn’t gotten very far up Broadway when I finally got a telephone call through to my parents at their home in Louisiana. In my message, I said “I don’t know if you realize this but some planes hit the towers. I’m okay! Please get in touch with my husband, call my brother, tell them I’m safe,” and then it cut off. By the time they were sent home from work, my message was at their house but they couldn’t get through to anyone in New York, including my husband of two years.

My colleague and I walked up to Times Square and I saw on the big screens that my building had fallen. From there we walked all the way to 61st Street to my husband’s uncle’s apartment, where I sat down for the first time that day and watched TV. He gave me a pair of sneakers because my feet were covered in blisters from walking 80 blocks. That’s when I figured out what had happened at the Pentagon and with the flight in Pennsylvania.

At that point, I was safe and I thought, “What do I do now?” All my drafting tools from college were there, pictures, stuff like that. Thankfully my portfolio was at home but a lot of people had lost all their work effects. Though we had lost our office, my company was set up and running in a week and a half. They called us on the Thursday after, and said “We’re not going to shut down. We’re a family. We’re going to take care of each other. Take the time you need and come back to work when you’re ready.” Some people didn’t come back.

But we couldn’t have resumed work without the support of the design community. One of our clients gave us half a floor and set up little workstations, and I worked on a computer donated by a competitor. Other firms donated phones. Since the back-up servers were in the WTC basement, we lost all of our files. Engineers showed up with discs saying “Here’s the drawings you sent me. I know you don’t have them anymore.” People just came together. It was very touching. We weren’t competitors: We were people taking care of each other.