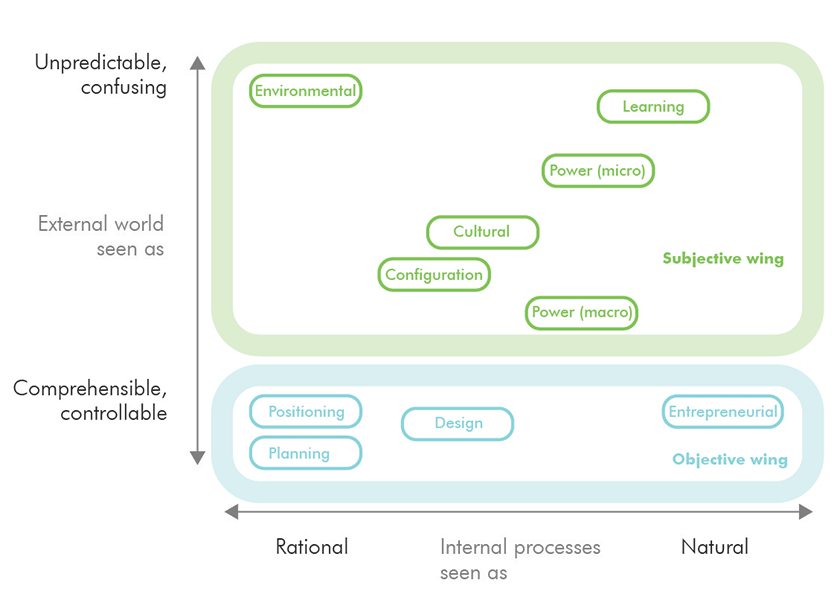

Workplace strategy can be defined through varying lenses in a subjective school of thought.

As discussed in Part I of “How To Think Like a Workplace Strategist,” there are varying schools of objective strategy that aid in solving workplace challenges. There are also a number of ways strategists can think through subjective lenses, or ways that view strategy formation as processes that emerge from the interpretation of a more confusing and chaotic world. The objectives school presupposes the world as comprehensible and controllable through objective lenses.

Learning is the most popular way of subjective thinking. Popularized in the late ‘90s, the Learning school argues that the world is too complex for strategy formulation. Instead, strategy is a process of “venturing,” or building fundamentals that help an organization learn and react efficiently. These fundamentals are often building information systems, organizational awareness, and hierarchical support. In the midst of the workplace strategy, today’s parallel is building a framework, often with HR and IT, for transparent and continued feedback on how the facility—outfitted with a flexible kit of parts—is responding to changes in its environment. Technology start-ups are perhaps the widest adopter of this type of strategic thinking. The danger with this approach, however, is the possible disintegration of strategy, leading to no/lost/wrong strategy emerging from “groupthink,” which can quickly escalate commitment, and time possibly wasted.

The Power school posits that strategies can be formed through corporate political positions and ploy. All workplace strategists deal with Power on a micro level, from adjacency to workstation/office size to space allocation. When we think bigger, Power also comes in a more macro form of strategic alliances such as partnerships, shared distribution, and technology transfers. The popular co-working business model is an example of thinking about Power on a macro scale.

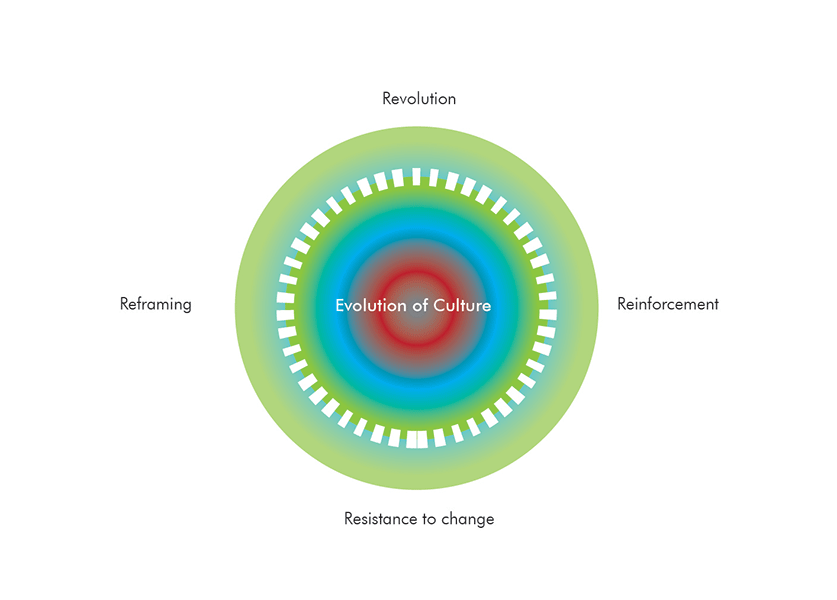

Strategy within the Culture school takes the form of perspectives rather than artificial positions that need to be created. However, strategists can still help organizations recognize the danger of a stagnant culture that discourages requisite change and helps reframe perspective. A workplace strategy parallel would be Marissa Mayer ending the work-from-home policy at Yahoo! in order to drive a more collaborative and faster-paced culture. Of course, a strategist should also help reinforce the culture during a period when change is not needed. As Peter Drucker famously said, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

The Environment school of thinking is similar to the positioning school in that it argues there are only a few rational strategic positions within the existing ecosystem. The workplace parallel is more applicable in the world of real estate portfolio and work force analysis. For example, a company may place its call-center staff in a geography with lower cost of living. Though necessary and popular among the more analytical strategists, this school of thought is often criticized as restricting strategic choices.

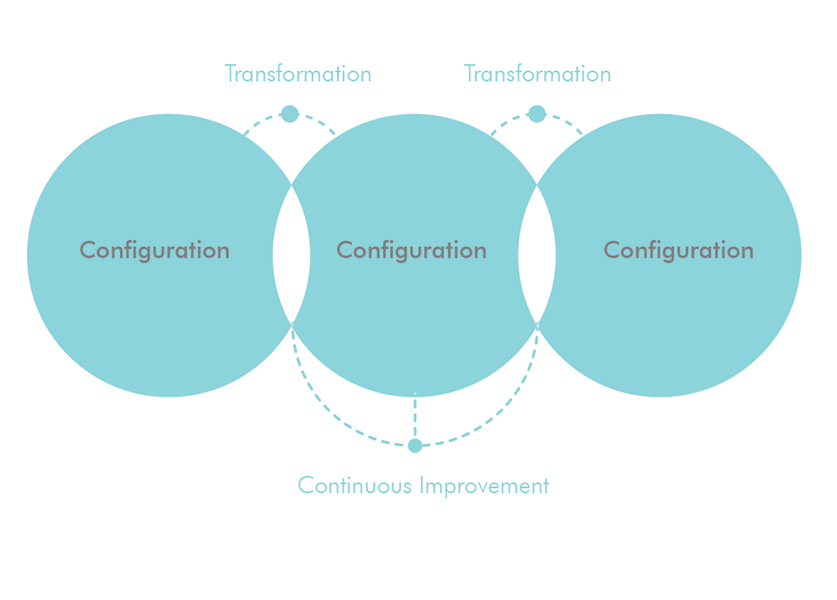

The Configuration method takes a longer view at strategic transformation. The premise is that an organization’s strategy at a particular point in time results from a combination of schools of strategic thinking (outlined here and in Part I). In Configuration thinking, the strategist’s role is to sustain stability of the configuration, and help the organization recognize the need for transformation, and manage what can be a disruptive process while supporting both old and new features of the organization.

This last school of strategic thinking highlights the importance of change management and the strategist/designer’s role in developing an inclusive design process that works with all levels and functions of an organization, including HR and IT. One of the biggest and most transformational projects that jumped from one configuration to another would be US Federal Government which has developed Workplace 2020. This program comprehensively changes everything about how and where people work, and how policies, processes, technologies, and facilities are imagined and managed.