IA’s global presence provides its clients comprehensive workplace practices with regional nuances.

When IA was established in 1984, founder and President David B. Mourning declared the company would operate on the client-first principal: “Our clients come first,” he has said on numerous occasions. Providing the best professional services possible to clients—existing or new—was the firm’s top priority. And as its clientele expanded and grew, IA established offices overseas to fulfill the wishes of its international partners.

“We’re always aligning ourselves with our clients’ needs,” says Bill Rutkowski, managing principal of IA’s London office. Having worked in IA’s New York office for a number of years prior to relocating to the UK in 1997, he says there are many similarities between the two cities. But the biggest difference is the phenomenon of the office cube: It never struck London.

“The Dilbert effect never hit Europe, save for the American companies that specifically requested it,” Rutkowski says. “Over the years in London, it’s always been desks lined up in rows: Bob Cratchit sat at a desk!”

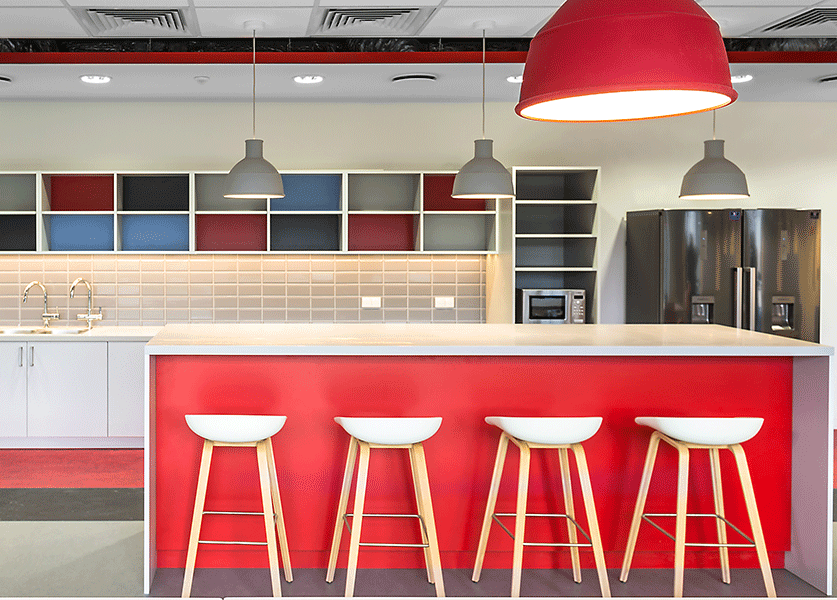

Part of the reason for this difference is that raised floors have always been prevalent—more so than in the United States. Freedom of access for wires and cabling permitted furniture to be lighter and more flexible. There was less of a need to channel cables through cubicle walls. “Although IA is a global firm, we are a US-based company, so we’ve had local, British clients ask us on occasion if we could please avoid specifying cubicles; they prefer light and openness,” Rutkowski laughs.

There also tends to be greater square footage per person in the UK, as opposed to the US. This is in part due to codes: London is a tight, crowded city with narrow streets and tight spaces, originally designed as such by the Romans. When the Great Fire of London leveled the city within the walls in 1666, approximately four days of conflagration consumed nearly all of the buildings of the City Authority—the commercial buildings of that time. Occupancy codes have since been established with increased sensitivity to density for greater flexibility with fire evacuation routes.

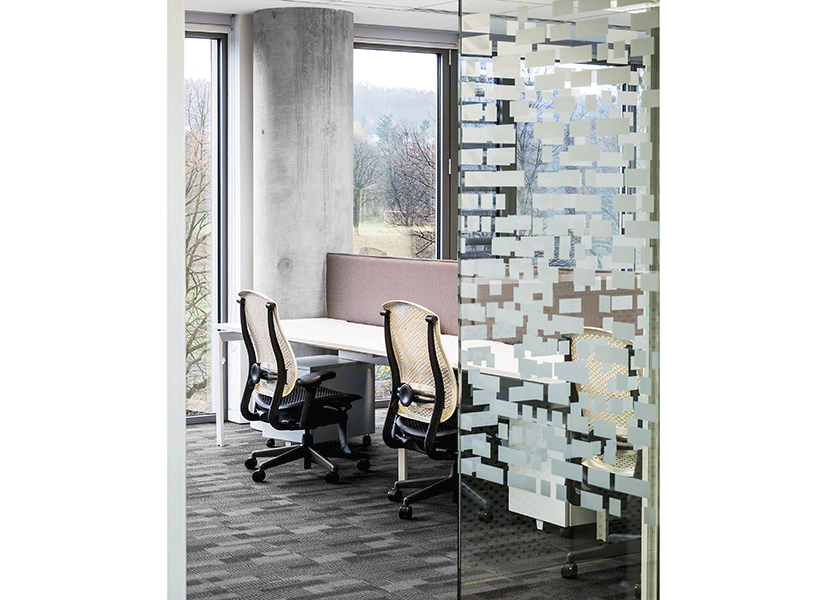

In continental Europe, codes also require particular access to daylight. Commercial buildings tend to be longer and skinnier, instead of boxy with deep floor plates. “In Holland, for example, office buildings look like hotels because the law says workers have to be a certain number of feet away from a window,” Rutkowski says. European and Scandinavian countries set strict daylight access requirements: Office buildings must feature vertical glass surfacing that totals at least 5 percent of programmable square footage.

But similar to the US, workplace design paradigms are shifting in favor of task-based spaces and flexibility to adapt to different duties. “It’s based on need,” Rutkowski says. “Instead of everyone getting the same kind of desk, or a scenario where space is awarded according to hierarchy, it’s more about who needs what.” Settings from private “think” rooms to collaborative lounges are all common space typologies in the European workplace.