Until the creation of National Gargoyle Day (for which we might start lobbying), there will be no more fitting time of year than Halloween to discuss the merits of the humble gargoyle. The version of this mythological beast that most of us think of has its roots in medieval Europe, and the word itself claims French parentage, likely from the Old French word for throat, gargoule, with older Latin roots that lead to words like gurgle, gulp, and gullet. The design of these rooftop creatures is the direct result of medieval construction methods and in particular the qualities of cured lime mortar. While a number of ancient cultures had created water-resistant mortar mixtures for use in construction, those recipes didn’t make it to Europe until well after gargoyles had been added to the architectural lexicon. Since medieval construction relied upon a mortar that tended to degrade upon prolonged exposure to water, builders had to devise creative methods for diverting water away from the structures. This explains why most gothic gargoyles you’ll encounter will have long necks and why so many of them function as rainwater spouts.

A gargoyle from the Pilori building at Niort, Poitou-Charentes, France. Photography © Dynamosquito. This image was marked with a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

That’s not to say that gargoyles are the only creatures you’ll see saving gothic structures from errant rainwater—plenty of buildings feature statues or water spouts with likenesses of snakes, dragons, griffins, clergymen, and even the occasional architect.

A gargoyle at St. Vitus' Cathedral in Prague, Czech Republic. Photography © Vin Crosbie. Photography is marked with CC BY-ND 2.0 license.

Uncertain Roots

Although most origin stories of the gargoyle mythos seem to center around St. Romanus of Rouen and his battle with a particular type of dragon, humans had been decorating rooftops with stylized animal likenesses for millennia before this story ever took place. Ancient Indian, Roman, Grecian, Egyptian, and Turkish peoples all utilized animal likenesses to draw water away from buildings (and in all of these examples the animal most often symbolized was a lion). While a number of other cultures adopted the practice of adorning their roofs with ornamental animals or likenesses, here are a few examples with which you may be less familiar.

A shisa on top of Nakamura's house in Kitanakagusuku, Okinawa Japan.

Rooftop Shisa or Shishi

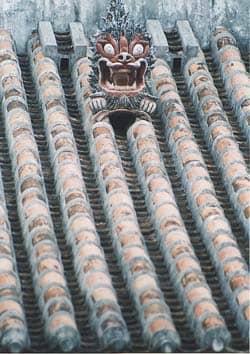

Featured most prominently in Okinawan and their culture, shisa are mythological creatures that were placed, often in pairs, on rooftops or over gates to ward off evil spirits. Sharing roots with Chinese shishi (Chinese stone lions) and Korean komainu, shisa are represented in many East Asian cultures (although these other variants aren’t typically seen on roofs).Onigawara and Shibi

An onigawara seen in Tokyo, Japan. Photography © Haragayato. Image is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5

Also hailing from Japan, onigawara usually functioned as a form of shibi (decorative roof statue) positioned along a roof’s ridgepole and featuring the likeness of a Japanese oni (comparable to an ogre, demon, or troll). Rather than diverting rainwater or being purely decorative, however, onigawara reduced the likelihood of a leaky roof by reenforcing the roof’s ridgeline with waterproof material (stone or hardened wood).

Chiwen, Chaofeng, Chishou, and Shachihoko

Chiwen on the roof of the Hall of Supreme Harmony, at the Forbidden City, Beijing.

Several stories in Chinese mythology dating back to at least the Ming Dynasty outline a dragon with nine sons. Of those nine dragons, several are often featured prominently in architecture, and two of them could be compared directly to gargoyles—chiwen and chaofeng. While each of the nine dragons have their own traits and protective qualities, chiwen are known for protecting buildings from fires (and are often placed on ridgepole ends), and chaofeng are adventurous creatures often seen on roof ridges.

Pixiu and other creatures also often grace the four corners of Chinese structures, and eventually influenced the Japanese shibi, which are another ornamental ridgepole tile that often took the form of tiger-carp hybrids called shachihoko. Forms of this design element can be seen in Western design and architecture as part of the Chinoiserie movement, which accompanied the tea trade from Eastern Asia to Western Europe.

Koruru

A koruru gracing the top of a structure in Korinti, New Zealand.

Koruru are features of Māori architecture and are also called gable masks. Traditionally, these masks do not reference animals. Affixed to the front of wharenui/tipuna whare (ancestral meeting houses), and other structures, they were meant to resemble a notable ancestor. Koruru were generally very abstract representations of ancestors, and, like gargoyles, have their own fantastic origin story.

Toritos de Pucara (little bulls of Pucara)