The research team operated out of the University of Gävle, with help from teams at the University of Central Lancashire and RWTH Aachen University.

Researchers at the University of Gävle recently completed a study that aimed to identify why background conversation is such a distraction in the workplace and whether or not exposure to background phone conversations is better or worse than exposure to full dialogues. Citing previous studies that demonstrated the negative impact of such noise on health and productivity, the team knew that, in general, they would find a significant, negative impact on productivity. They also had reason to believe that overheard phone conversations (called “halfalogues” in the study) might be particularly distracting. By giving a team of volunteers tasks designed to mimic those that “office workers might undertake in a busy open-plan environment” and simulating an office environment, they planned on isolating why this might be the case, and what might be done to mitigate that impact.

The Experiment

Previous experiments established two prominent theories explaining why phone conversations were particularly irksome—Acoustic Unexpectedness and Semantic (Un)Predictability (see figure 1.1 for definitions). To test which theory was the most likely culprit, they created a simulated office, complete with pre-recorded background conversations and several tasks used to judge worker productivity.

Figure 1.1

Acoustic Unexpectedness – Phone conversations are distracting because, since the other person is not within earshot, you can’t predict when speech (noise) will occur, and regardless of what is being said, this surprise makes it difficult to accomplish complicated tasks.

Semantic (Un)Predictability Hypothesis/Need to Listen – Phone conversations affect bystanders’ cognitive performance because of an implicit human need to complete knowledge gaps and therefore attempt to predict what is being said by the person on the other end of the line.

The Results

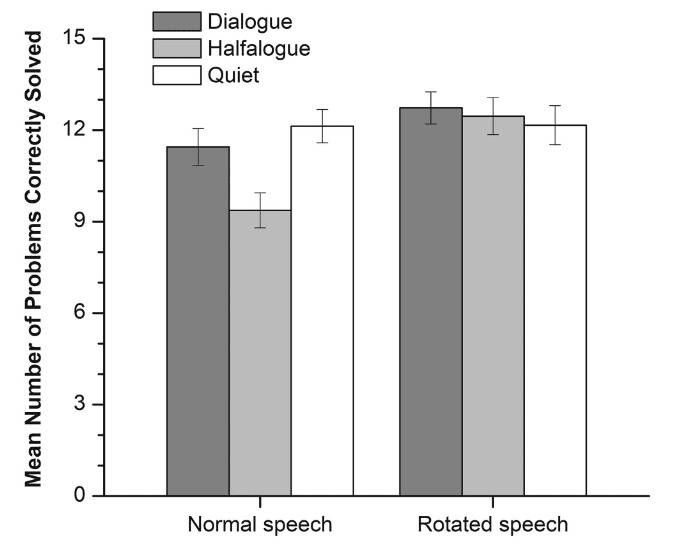

Results not only verified that halfalogues were more of a distraction than dialogues, but also that when such conversations were conducted in intelligible speech (a recognizable language versus a foreign language, for example) they proved to be more distracting to users. Most importantly, this data supported the semantic (un)predictability model of thinking, meaning that background phone conversations are more distracting because of a user’s need to understand, and likely attempt to complete, half-heard conversations.

The Implications

1. Workplace strategists now have a measure by which they can gauge the impact such an environment might have on productivity—in the case of this study, approximately 30%. This measure will help in determining the placement of work stations in future projects.

2. The study supports claims made by many sound masking systems that masking sounds to the point of unintelligibility may directly improve productivity. The paper is careful to also state that this study in no way tests for the impact of high levels of more general noise. That said, it can be assumed that real-life work environments under circumstances similar to those in the study would find the implementation of a sound masking system beneficial in combatting the distracting nature of background phone conversations.

Figure 1.2

Courtesy of APA.org

3. While not emphasized in the report, the data hints that there may be a positive relationship between productivity and exposure to unintelligible dialogue, which may have interesting implications for where workstations are placed for specific work types.

Call and customer support centers, like the one pictured above, are particularly susceptible to what the study calls the halfalogue effect. Peloton, Plano, TX. Photography © Thomas McConnell.

The study implies that sitting near ongoing, unintelligible halfalogues may marginally benefit work productivity. Confidential Client, Houston. Photography © Peter Molick.

Technically speaking, the results imply that working near a meeting area where acoustics dampen (to the point of unintelligibility) but don’t wholly erase predictable noise may actually improve one’s productivity. Naturally, further research would be needed to fully support such a claim, but this may effect for example, the placement of heads-down, individual work areas near meeting spaces.

4. A secondary aspect of the study discovered that making task completion more difficult by writing tasks in a harder to read font (referred to as “introducing levels of disfluency”) actually combatted the adverse effects of exposure to background noises. While this in itself doesn’t impact the design of workspace, it does open up the possibility that intentionally-designed instances of disfluency in the immediate work area could improve task completion by employees in open-plan offices. Future research is highly unlikely to find that - as a hyperbolic example – impractically designed desks might erase the impact of background noise. But, this study may lead to future research on whether specific patterns, textures, materials, or lighting solutions can serve to help users concentrate better when completing tasks while subjected to halfalogues.

5. Perhaps most obviously, this study supports the strategic use of phone booths and other acoustic solutions to phone-based noise in the workplace.

A private meeting space like this one in New York City could help decrease the impact of overheard conversations, and increase team productivity. Confidential Client, New York. Photography © Magda Biernat.

Acoustically sound spaces for taking phone calls diminish the "halfalogue effect." Confidential Client, Houston. Photography © Thomas McConnell.

Conclusion

Ultimately, when viewed through the workplace design lens, this study may fall into the category of research that is exciting because of the research that it will lead to, but those who aren’t inspired by that should find some solace in knowing that they are completely justified if they find their coworker’s phone conversations to be, if not completely annoying, at least 30% distracting.