Workplace planners and designers need to establish a system of analysis that supports continuous change.

I am a big supporter of benchmarking because it is a powerful tool to ignite change. However, the way it is perceived—and sometimes executed—in the workplace design industry is flawed and could lead to the wrong type of change, or no change at all.

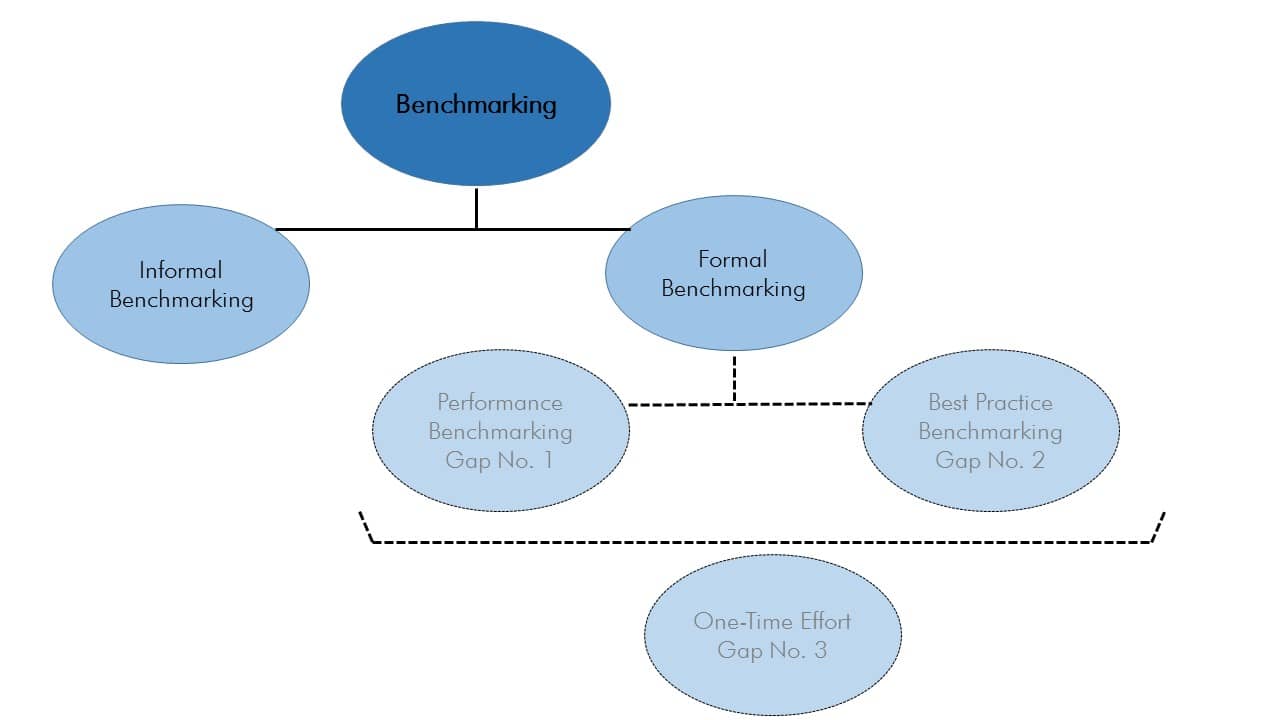

According to the Global Benchmarking Network, benchmarking is a methodology that can be classified into two main categories: Informal and Formal benchmarking.

Informal benchmarking is an unstructured approach to learn from the experience of other organizations. For instance, we can cite the observation of Facebook’s new Building 20 as the new benchmark of ultimate flexibility because it boasts what is allegedly the largest open office plan, or the example that more companies are choosing to open offices in urban centers.

Formal benchmarking is conducted systematically and can be further subdivided in two categories: performance benchmarking and best practice benchmarking.

Performance benchmarking compares the performance level of a specific process. For instance, Amazon benchmarks their package delivery times against other online retailers.

Best Practice Benchmarking is searching for the best way by studying other high performing organizations.

Gap #1: Measuring the wrong metrics

The biggest gap is in performance benchmarking because clients and designers alike often measure operational metrics (e.g. square-footage per person or percentage of open office) that are inadequate for measuring overall effectiveness. For example, the client and designer could be perfectly happy with achieving a targeted density of 120 square feet per person because it meets cost efficiency criteria but the effect of the density is not measured as the output. How did the increased density increase employee engagement, productivity, attraction, and retention? Those factors still affect the bottom line.

Gap #2: Measuring against the wrong organizations

Best practice benchmarking is also typically performed haphazardly. This method should measure against select high-performance organizations, not everyone under the sun. Understanding how and why the select high-performance organizations arrived at that metric is also important, because if a competitor’s vision was flawed or restricted by an unknown factor we run the risk of copying flawed or low standards. For instance, a headquarters situated in a central business district would have vastly different amenity ratios because their design process would have involved consideration of amenities within the surrounding community.

Gap #3: Benchmarking as a one-time effort

Benchmarking is most valuable if an organization is structured to take advantage of it as a continuous improvement process as opposed to a project-by-project exercise. For example, an organization may perform a one-time benchmarking effort when constructing a new building, abandon the process after the project is done, and then perform the same analysis in three years when a new addition needs to be planned. A lot can change in three years. If an organization does not have the culture and associated structure and processes to support a continuous learning model, a one-time benchmarking process can deliver inconsistent results, introduce doubt, and increase barriers to change. Solving for this gap also helps to mitigate dangers of complacency. This is especially dangerous in real estate because it is a slow and punctuated field. An organization could be sitting on a “best practice” for many years while competitors leap-frog ahead.

The next time your organization wishes to conduct a benchmarking study, be sure to engage a consultant who will choose a smaller data set with more targeted competitors to measure against, and who demonstrates the knowledge and expertise to measure beyond space metrics. This, in parallel, will help your organization internalize benchmarking as a continuous improvement process so your effort continues to inform the organization’s evolution..