Part II of III

I went to Los Angeles and EPR won the IBM account for the Western U.S., but what was even bigger long-term was IBM’s concept of the “on-call” contract, or what we now call a national or global services agreement. It is defined as an arrangement wherein corporations pre-qualify architects and design firms to carry out work on an annual, contractual basis at preset fees in a matrix according to size and scope. This was a new approach for design firms and would be an integral business strategy when I established IA.

For me discovering the on-call concept might well have been the discovery of fire. No other corporations were applying this method of procurement; they were pre-qualifying, interviewing, and bidding architectural and interiors firms for every new project, and losing many weeks in the process. What was worse, they’d sometimes end up with firms that were not qualified to do the work. With this in mind, I went back to my banking clients and they hit the concept like a trout hits a fly. It was an immediate success.

“You mean I don’t need to go out to bid on every job?” they’d ask. “I can pre-qualify architects and only go to the legal department with a contract once a year?”

“That’s right, sir,” I’d assure them. Their relief was palpable.

Soon, EPR had a steady stream of business with not only IBM but all of the major banks in San Francisco as well. Months later, back in my boss’s office for a review, he again asked what I would like to do and I suggested we take the on-call concept national. “We should talk to IBM about serving their other regions,” I suggested. “And then we should go to Wall Street—that’s where the huge volume of work is.” Once more with his blessing, I fearlessly called on every major financial services firm in the Big Apple.

When I called on Merrill Lynch, it had an entire floor of internal architects, project managers, and draftsmen—a staff of 200 plus— at its headquarters at One Liberty Plaza. This team was responsible for all of the company’s branch projects in the U.S. After I explained the concept to Merrill Lynch’s head of real estate and showed him the matrix fee structure, it seemed as if a light went off in his head.

“What we now have in this department is a train station, and when we get a new project from an end- user at Merrill, we add another car to the end of the train,” he started to explain. “When that car, or project, gets through the station and is completed depends on how many staff we have. This makes for more and more staff, long delays, and lots of unhappy internal clients. But with your concept I can just add more trains!”

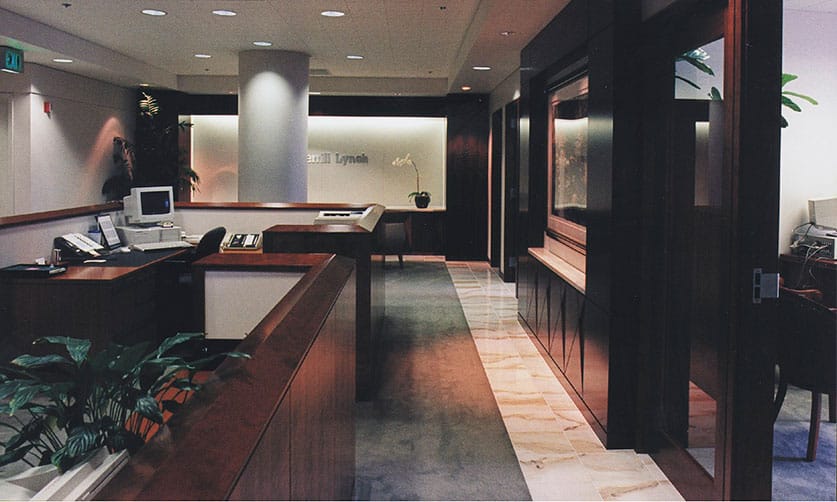

Within a couple of years, EPR was doing hundreds of projects across the country for Merrill Lynch. When IA was founded this contract came with me. To date, IA has probably completed close to a thousand projects worldwide over 30 years for Merrill Lynch, now under the ownership of Bank of America.

Additionally, I had been calling on Dean Witter in New York City. EPR had designed Dean Witter’s San Francisco offices, so I had an introduction to the company, but the head of its facilities department was a very difficult sell. I returned again and again over a period of several months and was summarily rejected each time. On what likely would have been my final sales call, I laid out the concept and benefits for Dean Witter. Once more, he looked at me directly and said, “Not interested!”

I packed up my papers to leave, but suddenly he stopped me in my tracks. “There is a little something you might be able to help me with. We were just acquired by Sears and they want to put a Dean Witter branch in all of their stores. Can you do that?”

“You bet,” I replied.

“Good,” he said. “The first group to do includes 92 branches.”

“Okay,” I said, gulping hard and thinking be careful what you ask for.

My EPR—and soon to be IA—colleague Mick McCullough got on an airplane to New York, promptly leased space, hired staff, and got to work on those 92 projects. That was the beginning of EPR’s New York office. Mick was the guy. He still is.

At this point, things were going very well. We had lots of new work, new clients and new EPR offices in New York and Los Angeles, but back at the headquarters in San Francisco the two founders of the firm had decided to sell EPR to an architectural firm in Houston. Over the next year we came to see why the saying that oil and water don’t mix is such an apt analogy. To call it an unsuccessful merger would be an understatement.

EPR was a great company and I can thank it for many things, but first and foremost, I learned to love the practice of interior design at EPR. I found it in many ways more creative, exciting, fast paced, and professionally rewarding than conventional base building design. I also recognized the practice of interiors to be more resistant to the economic cycles that cause revenue swings in most architectural firms. It was something with huge potential and I loved it. It was time to move on and establish IA.